A Buried Stream Runs Under It

By Rona Kobell

Wills Creek runs through Cumberland on its way into the Potomac River’s North Branch. Outside of town, it’s indistinguishable from the river it eventually reaches: wide and murky, with ample room for kayaks. Within town, though, Wills Creek is not a creek at all but a flood control structure. Its concrete bottom and steep, sidewalk-like banks channel water downstream. That water can rise quickly and run fast in heavy rains. There are signs not to enter it, not that anyone would find it inviting.

“Wills Creek is an example of a stream that was too big to bury, but they did their best,” said Andrew Elmore, an ecologist with the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s Appalachian Laboratory who maps and studies buried streams to gauge their effect on flooding and water quality.

A buried stream is a waterway that planning officials have decided should not be a stream anymore. Engineers route the flow through culverts and pipes. Then they simply pave over the engineered channel, building a road or highway. What was once an open stream becomes hidden. In Baltimore, the Jones Falls, a Patapsco River tributary, is one of the largest buried streams in Maryland; much of it sits under Interstate 83, also known as the Jones Falls Expressway.

Burying a stream causes problems for a waterway because it changes biological, physical, and chemical processes. Plants can no longer grow there, so they cannot absorb nitrogen and phosphorus from upstream sources or from air pollution dissolved in rainwater. Insects no longer hatch their eggs in the stream, decreasing their populations and depriving some fish of an important food source. A natural, meandering stream with vegetation and natural banks can remove nutrients and sediment from runoff on its way to larger rivers and the Chesapeake Bay. But in a buried stream, the concrete acts like a chute; rushing water from runoff, often filled with fertilizer, enters the waterways at a rapid rate. With no plants to take it up and no natural banks to slow the flow down, it carries these pollutants straight to the Bay.

Streams also exacerbate flooding. Even a buried waterway does not forget it was a stream. In a heavy rain, water fills up these channels; the water wants to go where it flowed in the past, even if that place is now covered in concrete and is near homes. That’s what happens on Valley Road, which runs parallel with Wills Creek in Cumberland, Md. and is next to a stream called Dry Run that’s often anything but. Valley Road and Wills Creek together dive under the city, part road and part stream, not successfully performing either function well on rainy days. Metal fences and rock dams attempt to control the flow, but often fail to do so. Valley Road wants to be a stream, ecologically, even if it looks like a street, aesthetically.

A decade ago, Elmore and his colleague, University of Maryland, College Park geologist Sujay Kaushal, began mapping the buried streams around Baltimore, focusing on the Gunpowder and Patapsco Rivers. They found that streams, in particular those in the headwaters, where they form, were being buried at a rapid rate. Planners and public officials often didn’t know where the streams were, or that they even had once been streams.

Having mapped the Baltimore area, Elmore and his colleagues turned to a much larger challenge: the Potomac River basin. The area they studied crossed West Virginia, Virginia, the District of Columbia, and Maryland. They found that patterns of stream burial are remarkably consistent: upstream, smaller streams are buried first, with a preference for low-gradient streams flowing through the best development sites.

Wills Creek starts out as a full-fledged stream of the Potomac, but is contained in a concrete flood control structure as it passes through Cumberland, MD. Here it’s a river surrounded by concrete.

Photograph, Nicole Lehming

It’s best, Elmore said, not to bury any more streams, and especially not to bury them when other streams in that area are already buried. The more managers can keep networks of streams together, the more connected the waterways will be, and the more useful habitat the plants and animals who depend on them will have. Managers need to know where the streams are, in order to protect them.

With climate change producing heavy rains and more flooding, Elmore said the country could use a detailed buried streams map sooner rather than later. He and his colleagues have been working with national policymakers to push for a map of both what has been buried and what is in danger of being buried in the future. They are hoping that agencies such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Geological Survey will be interested in creating buried stream maps for the whole country — to understand flooding in the buried areas and to perhaps compensate for habitat loss with restoration efforts.

“You have to have that tool, that map, if you are going to approach the problem,” Elmore said. “For any resource you want to conserve, you need to know where it is.”

—kobell@mdsg.umd.edu

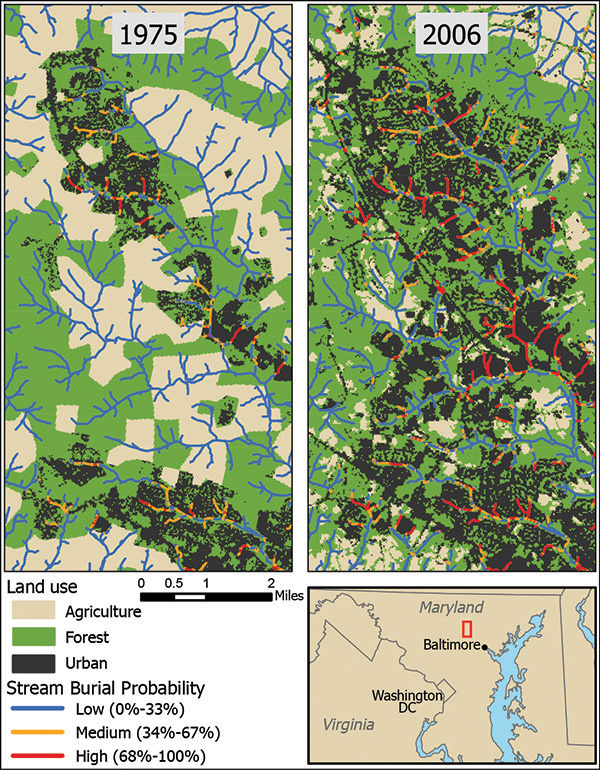

Topography Under Cover

Developing rural areas often results in streams being buried. They are directed into culverts, pipes, concrete-lined ditches, or simply paved over. Researchers at the Appalachian Laboratory wanted to find a way to better predict which streams would become buried as a result of urbanization. Using a new stream-mapping modelª that they developed, they incorporated field and remotely sensed observations with maps of impervious cover such as pavement. The researchers found that stream burial rates go up with increased urbanization intensity. Small headwater streams are among those most affected by urbanization because they are the most physically and economically feasible to bury.

This historical time series shows how the probability that a stream will be buried increased as urban intensity increased in the Washington, D.C. region between 1975 and 2006. The shading represents land use with the colored lines representing tiers of probability that a stream will be buried (blue 0–33%, orange 34–67%,

and red 68–100%).

ª For more information, see our article “To Map Streams for Restoration, First Go to the Source” in the April 2015 issue of Chesapeake Quarterly.

Graphic courtesy of Dr. Roy Weitzell, Chatham University

|