|

Saving Trees for the Forest

Jack Greer

"WATCH OUT FOR RATTLESNAKES. Don't put your feet anywhere you can't see."

Nancy Ailes has been "buzzed" twice already this year by rattlers. She loves to watch them. She says they're pretty lethargic. Usually. When an Allegany Trail power line crew recently found a nest of female rattlers and killed them, it upset her mightily. Rattlesnakes bear their young alive, she says, and the "mommies" gather in nests to protect them.

|

|

Back home in West Virginia, Nancy Ailes devotes time and talent to saving rural lands in the watershed of the Cacaponand Lost rivers. She's racing against a wave of population and development that spreads west from urban centers like Washington and Baltimore.

Credit: Jack Greer. |

She marches through tall grass. It's hard to keep up and still watch your feet.

Ailes is making the rounds today, checking out forests and fields she's been trying to save for nearly a decade. The threat she fears is not rattlesnakes, but development.

This part of West Virginia, as wild and wonderful as the slogans would have it, is within striking distance of the highly populated Eastern seaboard and the sprawling cities of Washington and Baltimore. Many of the homes built here recently, she says, are second homes for people who live and work in those nearby cities. As the head of the Cacapon and Lost Rivers Land Trust, she works on convincing the locals — farmers and other landowners who still live here — to give up their development rights to ensure the future of this rural landscape.

Nancy Ailes loves this land, rattlesnakes and all. She grew up in nearby Romney, West Virginia "on the back of a horse." When she was about seven or eight, her father taught her to fly-fish in local streams. Now her worst nightmare is that the farms of her youth will begin to sprout houses, and the forests around those farms will fall to make way for residential subdivisions and recreational developments. She fears that what's natural and homegrown about this place will disappear.

It's a realistic fear. Land preservation is a tough task in this neck of the woods. Much of this landscape belongs to farmers who grew up here. But many are already struggling with rising production costs and the falling prices bequeathed by global competition. For many, their land is their savings account and their stock portfolio rolled into one.

The air smells clean here. From the middle of the field Ailes points out a fenced area, part of a habitat restoration project — one of the watershed's successes. And she can see, on the other side of the fence, land that's yet to be saved. All through these valleys and along these hillsides there are fields and forests with pretty views ripe for development.

With premature white hair and bright eyes, Ailes is still this side of 60. As she walks through this broad field surrounded by ridges, she appears to draw on a deep well of energy. A natural-born hiker, she trekked Yellowstone National Park from top to bottom with her husband, ecologist George Constantz. And then they hiked it from side to side. Over the past seven years, they also took on Jasper, Banff, and other parks. All told, they hiked some 1,200 miles with packs on their backs.

|

|

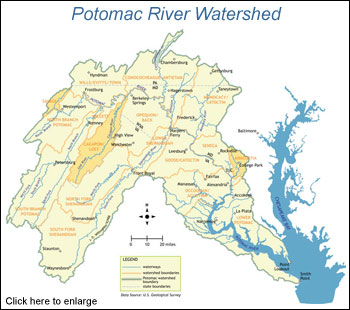

Second only to the Susquehanna, the Potomac River, drains a 14,670 square-mile swath of the Chesapeake watershed. In the center of the western ridge-and-valley terrain, the catchment for the Cacapon and Lost rivers rises like a teardrop. The heavily forested Savage River basin fringes the very edge of the watershed in far western Maryland. From the upland reaches to the Washington suburbs, saving forests offers the best hope for improving water quality in "the nation's river" — and in the Chesapeake Bay. Click on the image to view a larger version.

Credit: Map created by Jennifer D. Willoughby, Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin |

But her usual stomping ground is here along the eastern edge of West Virginia, near the Virginia line and just south of the panhandle, a shank of the state that juts east between Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland. It's beautiful here, both farm country and mountain country. Much of this is grazing land, rolling grassland surrounded by trees. It's the trees that make the ridges green, miles and miles of forest.

Her work in these uplands is part of a battle to save the landscape. It is also work that will help save the Chesapeake Bay.

When rain and melting snow run off this part of West Virginia they sooner or later spill into the Cacapon River. At Paw Paw, West Virginia, the Cacapon joins the Potomac. When the Potomac hits Great Falls, it roars over the cataracts and lands in tidal waters, delivering its load of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment to the Chesapeake. That deadly trifecta of dirt and nutrients has altered the ecology of the estuary, darkening its waters, robbing its seagrasses of sunlight, creating dead zones every year along the bottom.

The forests Ailes wants to save serve as important buffers — taking up nutrients, binding carbon, evening out the flow of surface waters, and protecting streams against flashiness, eutrophication, and overheating. Forests perform so many "ecosystem services" throughout the six-state Bay watershed, that scientists in a 2006 report on the state of the Bay's forests estimated their ecological value at some $24 billion a year.

Saving forestland has emerged as one of the best ways to restore water quality in the Bay's tributaries. And one of the best ways to save forests is to stem the tide of sprawl development. Conservationists and others — after watching a degraded Chesapeake fail to improve after more than a quarter century of commitments and restoration efforts — are counting on Nancy Ailes and others like her to preserve the region's open lands and especially its forestland.

The challenge she faces each day is convincing farmers and other landowners to give up their development rights to preserve this watershed's farm and forestland. Whether her efforts ultimately succeed will depend on her continued passion, her skills as a negotiator, and on the willingness of those who own the land to forgo potential profits for the greater good — for the good of the land.

Saving forests here is like holding the line in an ecological battle. After all, it's here in the western reaches that most of the Bay watershed's large tracts of forest remain. And according to the Chesapeake Bay Program, the Bay watershed is losing more than 100 acres of forest a day.

How are forests doing out here? How healthy are they?

High overhead a hawk pierces the afternoon with its sharp cry. Ailes shades her eyes to look up. Probably a redtail, she says. The hawk wheels toward a high ridge, toward where autumn-tinted trees stretch way off to the west.

A Life in the Trees

It's the first day of bear season, but Keith Eshleman doesn't think about that. Not until a ranger in a pickup rumbles down the rocky access road and pulls up with his arm out the window. Yep, first day of bear season. Probably should be wearing an orange hat. Or vest.

The access road — meant for rangers and off-road vehicles — runs along Poplar Lick, a bright mountain stream that lies about ten miles west of Frostburg, Maryland. Poplar Lick flows into the Savage River, which means that like the Cacapon River, it's a tributary of the Potomac. On this October morning it gurgles with rainwater filtered clean by leaf duff, roots, and all that's buried beneath the forest floor. Along this stream the trees look hardy. Hemlocks grow dark green. Ash leaves flash burnt yellow.

Eshleman, who's on foot, has come to observe several streams and to check one of his many monitoring stations. A hydrologist, he's spent nearly 15 years in Frostburg at the Appalachian Laboratory, part of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. In this mountainous countryside he studies connections between woodland streams like Poplar Lick and the health of the forests that surround them. It's a great laboratory for testing how forests affect watersheds.

|

|

Taking the pulse of mountain streams, Keith Eshleman tracks the health of the forest by looking for telltale signals in the quality of the water.

Credit: Jack Greer. |

As he walks along the stream, he picks out ash and beech and shagbark hickory. He taps black cherry trees with trunks as big around as oaks. For a hydrologist, he seems unusually fond of trees.

His team operates 7 stream monitoring stations in Western Maryland forests and 3 more on mine land. He also tracks a number of monitoring stations in the Shenandoah National Park, including 40 on Paine Run alone. Most of the readings he gets from his forested sample sites have remained fairly stable over many years. That stability allows him to pick up small changes. He says that after a good rain he can spot sediment signals even from small farm fields or eroding backyards.

|

|

Monroe Run passes through forested hillsides once bared by heavy logging. Now gray patches reveal another threat, oak branches stripped by gypsy moths. Click on the image to view a larger version.

Credit: Jack Greer. |

The Savage River watershed, of which Poplar Lick forms a part, is now more than 80 percent forested, but it wasn't always so heavily treed. Early in the 20th century, after heavy logging, these hills stood bald. The trees have come back, and Eshleman now describes these forests as well established, full of bear and other wildlife, and well above the 70 percent coverage needed for good stream health.

But some of his monitoring data have picked up worrisome changes in the trees, not just here but in other watersheds as well. After a steep drive uphill from Poplar Lick to the Monroe Run overlook, he points to the problem. On the right-hand ridge, bare limbs show up as patches of gray. These leafless oaks are not just dormant, they're dead. Victims of the gypsy moth.

This troublesome insect arrived in New England in the late 1860s, courtesy of a scientist named E. T. Trouvelot. Trouvelot hoped to breed gypsy moths with other moths to create a new strain of silkworms. Instead he spun a nightmare. With few natural enemies, the gypsy moth moved west and south — recently aboard trailers, campers, trucks, and cars . . . wherever the wandering moth might lay its eggs.

Eshleman says that gypsy moths hit these forests with a double whammy. Forests cover large stretches here, but the woods are literally moth-eaten. Because they defoliate and kill so many trees, the moths thwart the forest's knack for taking up nutrients and sequestering carbon. Then, adding insult to injury, the feasting caterpillars excrete large amounts of "frass" — waste that's rich in organic nitrogen and carbon. So just as the forest loses much of its capacity to handle nutrients, the caterpillars drop a heavy load.

|

|

|

|

|

FROM HILLSIDES TO SHORELINES, trees filled the Chesapeake Bay watershed to the brim when the first Europeans planted their roots in the 17th century. Forests covered nearly 95 percent of the land. But by the turn of the 20th century, logging and agriculture had felled 60 to 70 percent of the watershed's lush forest cover.

Today, forests make up an estimated 58 percent of the watershed, according to the regionwide Chesapeake Bay Program. A marked improvement from 100 years ago, but still far from what experts say is needed for a healthy Bay. [more] |

This is what his monitoring stations have told him. When moths defoliate the trees, in-stream monitors pick up rising levels of nitrogen.

The trend is alarming. These forests face a number of exotic enemies, he says — not only the gypsy moth but the emerald ash borer and a woolly adelgid that attacks hemlocks. In places not protected from harvest, trees also face the chainsaw. In some areas of the Bay watershed, forests now resemble a patchwork quilt.

These forest disturbances damage more than the trees. They hamper the ability of forests to take up nitrogen and phosphorus, their ability to protect the Chesapeake Bay. This is particularly damaging given that the Bay already suffers from too many nutrients, too much sediment.

He says that the loss of trees in forested bowls between ridges would be especially bad for water quality. Up here these hollows can send large amounts of rainwater toward streams and rivers. If disturbed by insects or chainsaws, forests will also send down big slugs of nutrients.

Eshleman says he appreciates the efforts of those working to restore forest buffers, but he doesn't think that saving riparian buffers is enough. Buffers can often be thin strips of trees, he says. "That may be important down near the Bay," but we're not just holding the line on nitrogen, he argues. We're trying to reverse current degradation. Forests are "anti-degradation," he says

Forests can take hits from exotic pests, chainsaws, and changing climate, if we give them space to respond. They can experience shifts in shape and species makeup, but with sufficient size and diversity they can be remarkably resilient.

Even when forests are disturbed, he says they're still the most "retentive" landscape we have — the best sponge for nitrogen and other nutrients. "We haven't gone far enough," according to Eshleman. "If we're serious about protecting water quality, we have to save what forests we have left."

Generations of farming run through the blood of Mike Rudolph (above). He and his brother have invested considerable time and money in best management practices, including a confined feeding station for cattle (right). Trees form the backdrop for his grazing lands — about 40 percent of forested lands in the Bay watershed are associated with farmland.

Credits: Jack Greer. |

Of Farms and Forests

Back in her dining room, Nancy Ailes sits down with Mike Rudolph. His family's farmed this part of West Virginia for three generations. The room is cozy, with a mountain view through wide windows. Rudolph seems mostly at ease, but he clearly has a lot on his mind. The local supply store sent him the wrong fence posts this week and he's had to reorder them. The guys he's working with on the fencing project are waiting for him, and there are decisions to make. During a long conversation, Ailes's phone rings. It's Rudolph's coworkers, calling about the fence.

Rudolph won't say so, but he has one of the biggest cattle operations in this part of West Virginia. His cattle graze different parcels of land in both Hardy and Hampshire counties. He's quick to explain the economic squeeze that he and other farmers feel every day.

"Imagine," he says, "that you were still making whatever it was you were earning back in the 1970s and trying to live on that in 2009. That's what farmers are trying to do." Beneath the visor of his Farm Credit field cap his blue eyes are piercing. "Farming's the only business I know," he goes on, "where you buy everything retail and then turn around and sell your product wholesale — and still try to stay in business."

|

It's in the harsh context of economics that Nancy Ailes speaks to farmers about putting some of their land in easement. |

According to Rudolph, the squeeze between what a farmer can get for his product and what he has to pay — especially for anything that's energy related — gets tighter all the time.

It's in this harsh context of farming and economics that Ailes speaks to Rudolph and other farmers about putting some of their land in easement. She asks them to sign legally binding commitments that will keep that land from being developed — forever.

A tough sell. But she argues that without this kind of intervention, farmland will disappear. The legacy of land that these farmers inherited will no longer pass to another generation. The watersheds of the Cacapon, the Potomac, and so many rivers that flow into the Chesapeake will lose their rural landscapes.

It's clear that Rudolph cares about the land. He speaks of local tracts with affection, telling their histories. There's a piece down by the river that might go up for sale. A big chunk up on the ridge that's already been sold. He's especially worried about a family that owns a lot of acres in the watershed — it looks like they might sell that property in pieces.

Sitting forward on her dining room chair, Ailes says that selling off property is a strong temptation, when land prices are high and times are tight. But she's shown that conservation easements can help farmers surmount the difficult financial hurdles of holding on to their land. She works with lawyers who identify tax breaks — savings in federal inheritance taxes, for example. The Land Trust is able to purchase a few of the easements, but most are donated. Her job would be easier if West Virginia offered state tax advantages for conservation easements, but so far that hasn't happened.

Are the slim incentives now in place enough to make the difference for a working farmer? Will someone like Mike Rudolph actually give up his development rights to protect the land in the face of financial uncertainty?

The Future for Forests

There is no doubt that the future of the Bay’s forestland lies largely in the hands of private landowners. According to the National Forest Service, some 64 percent of forested land in the Bay watershed is family owned. Businesses, by contrast, own only 14 percent. As the number of private landowners goes up — currently some 15,000 families and individuals — the size of the forest parcels they own goes down. For nearly 70 percent of all those private forest owners, their piece of the forest measures less than 10 acres.

In short, more people now own smaller plots. That may be highly democratic, but it creates a special challenge for those trying to manage forestland, and for those trying to protect the Bay's water quality.

HOW ARE TREES DOING IN THE BAY WATERSHED? 58 percent of the Bay watershed that is forested. 100 forest acres have been lost per day since the mid-1980s. 7.32 million acres of land have been preserved as of 2008. [more] |

It's easier to deliver to a few big landowners a convincing message about managing forests than to reach out to scores of new tree owners. That's why Nancy Ailes right away aimed for a few big spreads in the Cacapon watershed. By striking deals with a relative few, she was able to protect thousands of acres from development.

Now it's getting more difficult — for her and for many like her. To get a sense of the task facing the Potomac watershed, multiply the challenge Ailes faces in the Cacapon many times over. And even more for the whole Bay watershed.

Easements will be an important tactic in the fight to protect open lands from development, but they will not be the only tactic. Ailes's husband, George Constantz, founded the Cacapon Institute to focus attention on the health of the river and its watershed. Education. Advocacy. Technical assistance. These are some of the tools people like Ailes use to protect the land one acre at a time.

WHEN IT COMES TO FORESTS, STEPHEN PRINCE TAKES THE LONG VIEW. Prince and his colleagues produce maps that show where the forests are, and where they aren't in the Chesapeake watershed. One threatened forest lies just across campus from Prince's office. [more] |

Her tools, it seems, are working.

Mike Rudolph has put conservation easements on substantial portions of his land. And his brother, Jackie, has as well. He says they may do more. He says he doesn't want to see the land "broken up."

Because of farmers like the Rudolphs and others, the Cacapon and Lost Rivers Land Trust has now put into permanent easement some 10,000 acres — 10,000 acres protected from development in perpetuity.

With obvious emotion, Ailes tells the story of one farmer who was able, with their legal advice, to hang on to family land he'd inherited while saving it from development. The day he signed the conservation agreement he cried tears of joy.

For Ailes, saving the land from development is the essential first step. Yes, she says, there are other issues to take on. Fencing streams. Protecting woodlands. Redesigning feedlots. But if the land falls to development, pushing for better farming and forestry practices will be moot, because this will no longer be farm or forestland.

She estimates that about three quarters of easements here are forested. But how secure are the forests on these farmlands, especially along the ridges and in the hollows?

They are not completely protected, says Ailes, though the easements spell out strict requirements for a formal forest management plan before any harvesting can take place. That plan must have a goal for maintaining wildlife habitat and for promoting the "long-term sustainability of contiguous forest."

|

|

In a disappearing act, the Lost River for much of the year drops beneath a mess of boulders. When it reappears above ground it becomes the Cacapon. Nancy Ailes wants to ensure that the watershed’s farms and forests don’t perform a disappearing act of their own.

Credit: Jack Greer. |

Rudolph knows he can harvest his timber if he wants. For him, the trees on his property represent a "savings account," an account he can cash in if he has to. He says that he'd prefer never to do that, because "once you cash in your savings, they're gone." Besides, he likes the trees. The farmland around here has been about half working landscape and half forest for a long, long time. It's not likely to change.

Even so, unless he signs away his timber rights, the trees are his. There are no laws to protect them. Local limits on land use are not strict — in fact in this particular county, there is no zoning.

This is one of the key pieces to the forestry puzzle. Farms are currently one of the most polluting forms of land use, largely because they cover so much acreage in the Bay watershed. But farms are also home to many of the Bay's large patches of forestland. If farms break up and fall to development — to roads, subdivisions, schools, churches, shopping centers — that will mean more forest fragmentation. And worsening water quality for rivers like the Cacapon and other tributaries to the Potomac River and the Chesapeake Bay.

Nancy Ailes walks Rudolph out to his truck. There is hardly a sound to interrupt the silence between them. They both grew up in this ridge-and-valley terrain. They both formed a bond with this land long ago. Rudolph climbs into his pickup and cranks the engine. As he pulls off down the road, Ailes waves briefly before heading back inside. A light breeze rattles leaves around the house, a breath come down from that forest on the ridge.

|